Any post Bilski analysis needs to start off with the Supreme Court decision at the basis which of course is Bilsk v. Kappos 561 (U.S. _ (2010). The claims at issue here pertained to an invention which explained how buyers and sellers of commodities in the energy market could protect, or hedge, against the risk of price changes. Key claim 1 described a series of steps instructing how to hedge risk:

(a) initiating a series of transactions between said commondity provider and consumers of said commodity wherein said consumers purchase said commodity at a fixed rate based upon historical averages, said fixed rate corresonding to a risk position of said consumers;

(b) identifying market participants for said commodity having a counter risk position to said consumers: and

(c) initiating a series of transactions between said commodity provider and said market participants at a second fixed rate such that said series of market participant transactions balances the risk position of said series of consumer transactions.

Claim 4 merely put the concept articulated in claim 1 into a simple mathematical formula.

The remaining claims explained how claims 1 and 4 could be applied to allow energy suppliers and consumers to minimize the risks resulting from fluctuations in market demand for energy. For example, claim 2 claimed “the method of claim 1 wherein said commodity is energy and said market participants are transmission distributors.” Some of the claims also suggested familiar statistical approaches to determine the inputs to use in claim 4’s equation.

The Court started its analysis with Section 101 of the Patent Act itself which states that “whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title” .

The Court thus noted that section 101 specifies four independent cateogires of inventions that are eligible for protection: processes, machines, manufactures, and compositions of matter. However, the Court also noted that the Court’s precedents provide 3 specific exceptions to section 101’s broad patent-eligibility principles: laws of nature, physical phenomena and abstract ideas. While not specifically in the text of the statute, the Court noted that they are consistent with the notion that a patentable process must be “new and useful.”

The Court noted that the present case inovled a “process” under section 101 and that section 100(b) defines “process” as “process, art or method, and includes a new use of a known process, machine, manufacture, composition of matter, or material.”

At the outset, the Court rejected any categorical limitations on “process” patents such as the categorical exclusion of business methods patents or rigid application of the “machine-or-transformation test” which although useful should not be an exhaustive or exclusive test.

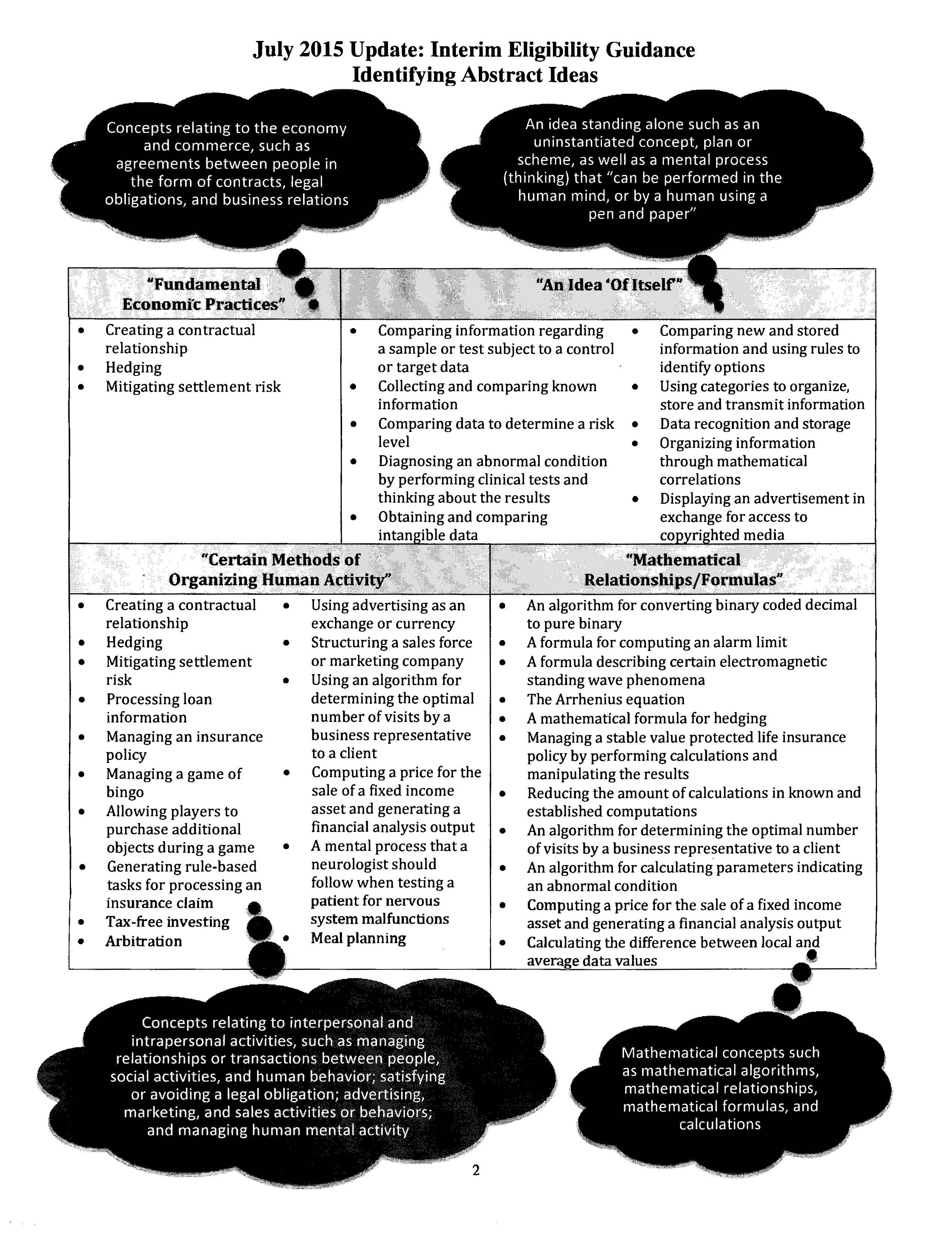

The Court instead rested its decision to reject the above claims on the basis that they claim an abstract idea. The Court noted in Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U.S. 73, 67, 72 (1972) which explained that “a principle, in the abstract, is a fundamental truth; an original cause; a motive; these cannot be patented, as no one can claim in either of them an exclusive rigth”. In that case the Court considered whether a patent application for an algorithm to convert binary coded decimal numerals into pure binary code was a “process” under section 101. The Court there stated that a contrary holding “would wholly pre-empt the mathematical formula and in practical effect would be a patent on the algorithm itself”.

The Court also discussed Parker v. Flook, 437 U.S. 584 (1978) where the applicant there attempted to patent a procedure for monioring the conditions during the catalytic conversion process in the petrochemical and oil-refining industries. The application’s only innovation was reliance on a maethmatical algorithm. Flood held the invention was not a patentable “process” because while, unlike the algorithm in Benson, the invention had been limited so that it could still be freely used outside the petrochemical and oil refining idustries, the Court rejected “the notion that post solution activity, no matter how conventional or obvious in itself, can transform an unpatentable principle into a patentable process.”

The Court then distinguished Diamond v. Dierh, 450 U.S. 175, 185 (1981) which claimed a previously unknown method for “molding raw, uncured synthetic rubber into cured precision products,” using a mathematical formula to complete some of its several steps by way of a computer. Diehr explained that while an abstract idea, law of nature, or mathematical formula could not be patented, “an applicaiton of a law of nature or mathematical formula to a known structure or process may well be deserving of patent protection”. Dierh emphasized the need to consider the invention as a whole, rather than “dissecting the claims into old and new elemetns and then…ignoring the presecne of the old elements in the analysis.” The Court distguished Dierh on the basis that the claim was not “an attempt to patent a mathematical formula, but rather was an industrial process for the moding of rubber products”.

Applying the precedent to the current case, the Court held that claims 1 and 4 explain the basic concept of hedging or protecting against risk. Hedging is a fundamental economic practice long prevalent in commerce and taught in any introductory finance class. The concept of hedging, described in claim 1 and reduced to a mathematical formula in claim 4, is an unpatentable abstract idea, jsut like the algorithms at issue in Benson and Flook. Allowing petitioners to patent risk hedging would preempt use of this approach in all field, and would effectively grant a monopoly over an abstract idea.

The Court state that the petitioners’ remaining claims are broad examples of how hedging can be used in commodities and energy markets. However, Flook established that limiting an abstract idea to one field of use or adding token postsolution components did not make the concept patentable. The claims in Bilski attempt to patent the use of the abstract idea of hedging risk in the energy market and then instruct the use of well-known random analysis techniques to help establish some of the inputs into the equation.